Hacking MiBand 3 for real, Part 2 - BLE

published in hacking

I’ve though that in this post I’ll focus on the entry point – the “Reset” handler – how it works and what it does. However I’ve noticed some very interesting looking strings in previous post that are worth investigating. Let’s quickly check them out!

Strings are for humans, part 2

Have you noticed the funny-looking strings with one or more percent % signs in it? If you had the opportunity to program in C (that one without classes) or PAWN (anyone?) before then you probably have guessed it already: they look like format strings!

Let’s pick one and find all the references to it.

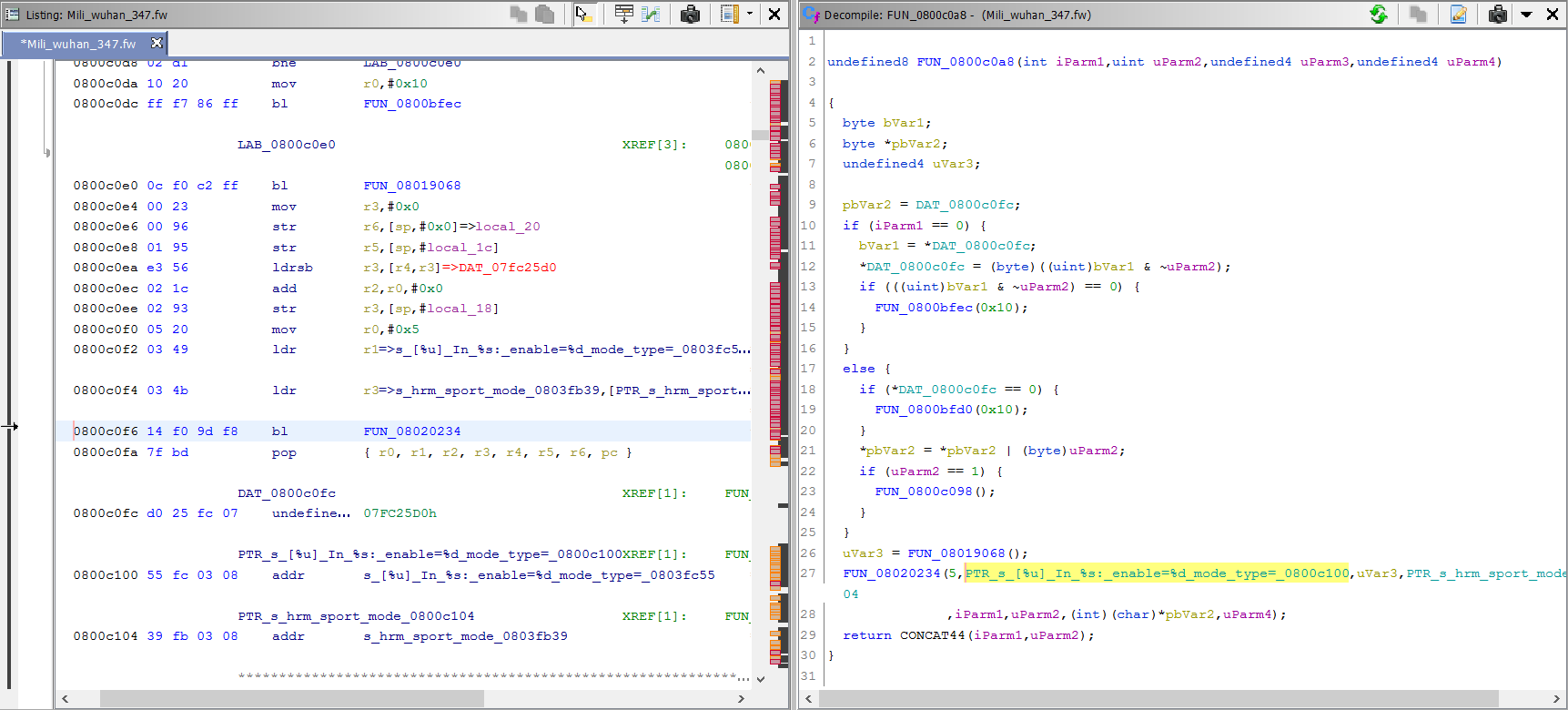

I’ve took "[%u] In %s: enable=%d mode_type=%d mode_mask=%d\r\n" from 0x0803fc55. We can clearly see that it expects 4 numbers and one string. Using Ctrl+Shift+F on it, we get a list of all references that use that string. The first found one (at 0x0800c0f2) is the one that’s interesting since we are loading it to the r1 register. Here’s the disassembly:

What’s more interesting, is the fact that this FUN_08020234() function is called from 139 different places. Most of the time the first argument is 5, regardless of the number of arguments, otherwise its 4.

Moreover the second argument its always a format string.

I’m thinking what you’re thinking: it must be a fprintf() function and the first argument is some kind of stream handle. Moving on.

Right after the format string there’s always the return value of FUN_08019068() function called just above. This function is called from 236 diffrent places! The used format specifier (%u) says it must return an unsigned integer. When we will decompile this function for the first time we would get:

undefined4 FUN_08019068(void)

{

return *(undefined4 *)(DAT_08019070 + 0x38);

}

which does not help very much. But if you look at other calls to this function, you’ll notice that sometimes its used within loops, and some of them also print a timeout message, therefore it must be time-related. My best bet would be something similar to GetTickCount(), but we don’t know its resolution yet. Nevertheless I’ve renamed that function to get_timestamp() with the optional suffix __GUESS until I’m sure its good.

The second format specifier is a string, but what for? In our case it points to "hrm_sport_mode" – interesting, since it looks like a C identifier. Moreover this function is the only place where this string is referenced from. Remaining arguments are basically taken from function arguments… What if this is the function name?

I’ve decided to look for a function that has two such fprintf()’s that use the same string, and there is one – FUN_080183a0() – which uses "ad_spi_write". They gave us some function and parameter names! Sweet!

PS: Keep in mind, that there might be some functions that use different “function names” but that might be just a hint that they’ve got inlined.

I would even expect that they defined some helpful preprocessor macro that utilizes

__func__or__FUNCTION__token. It could also prepend the timestamp to the format specifier.

The bad thing is that I don’t know where does those logs go nor how to access them. YET. I will definitely investigate it as printf() debugging is a really useful technique. Perhaps we will manage to send those logs via Bluetooth ;)

BLEssed strings!

We already covered translation strings and format strings, what’s left? I’m kinda getting bored covering those so I guess I’ll skip those looking like Java/Android package names and just focus on UUIDs:

00000005-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700

00000006-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700

9FBF120D-6301-42D9-8C58-25E699A21DBD

After doing some quick research, we know that the last one is related with Apple notification service. This leads us to BLE and its services. This could be fun.

GATT services can be exposed under a short ID assigned by Bluetooth SIG or a full 128-bit (random) UUID. Those strings that we see above use the latter format. Well, under the hood the former are being expanded to the latter one with "0000XXXX-0000-1000-8000-00805f9b34fb" (you can replace XXXX with %04x to get a format string). I can’t wait to see how those UUIDs are used in the code, so let’s investigate them further.

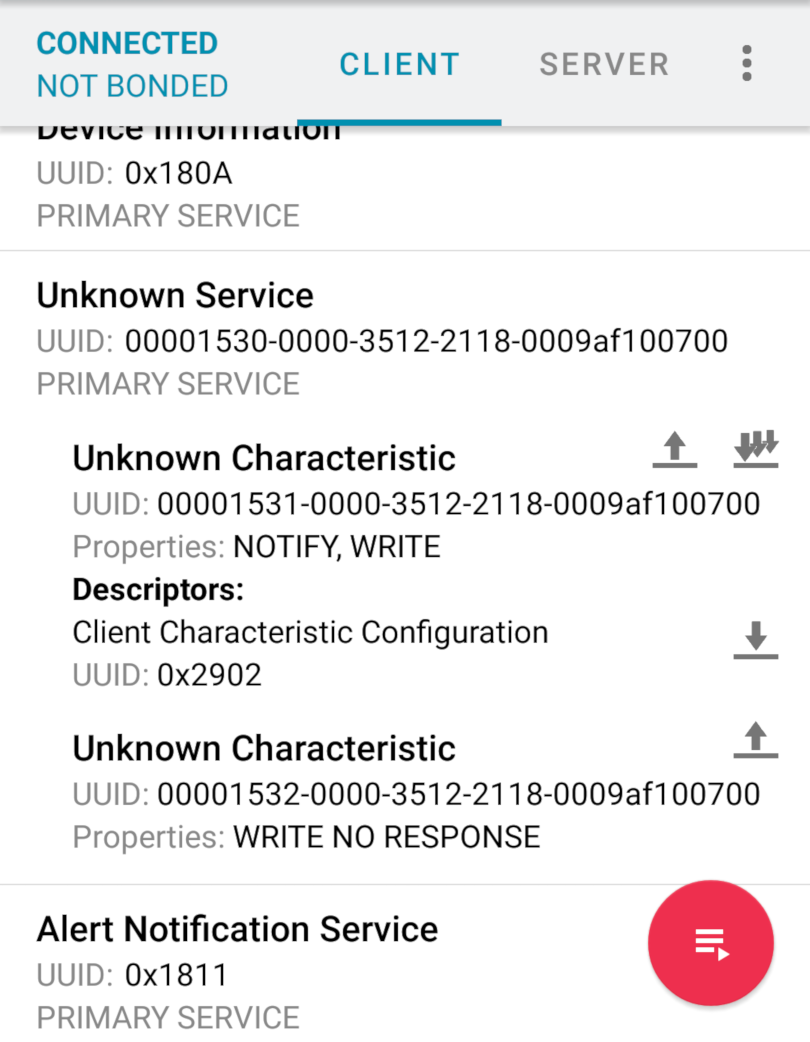

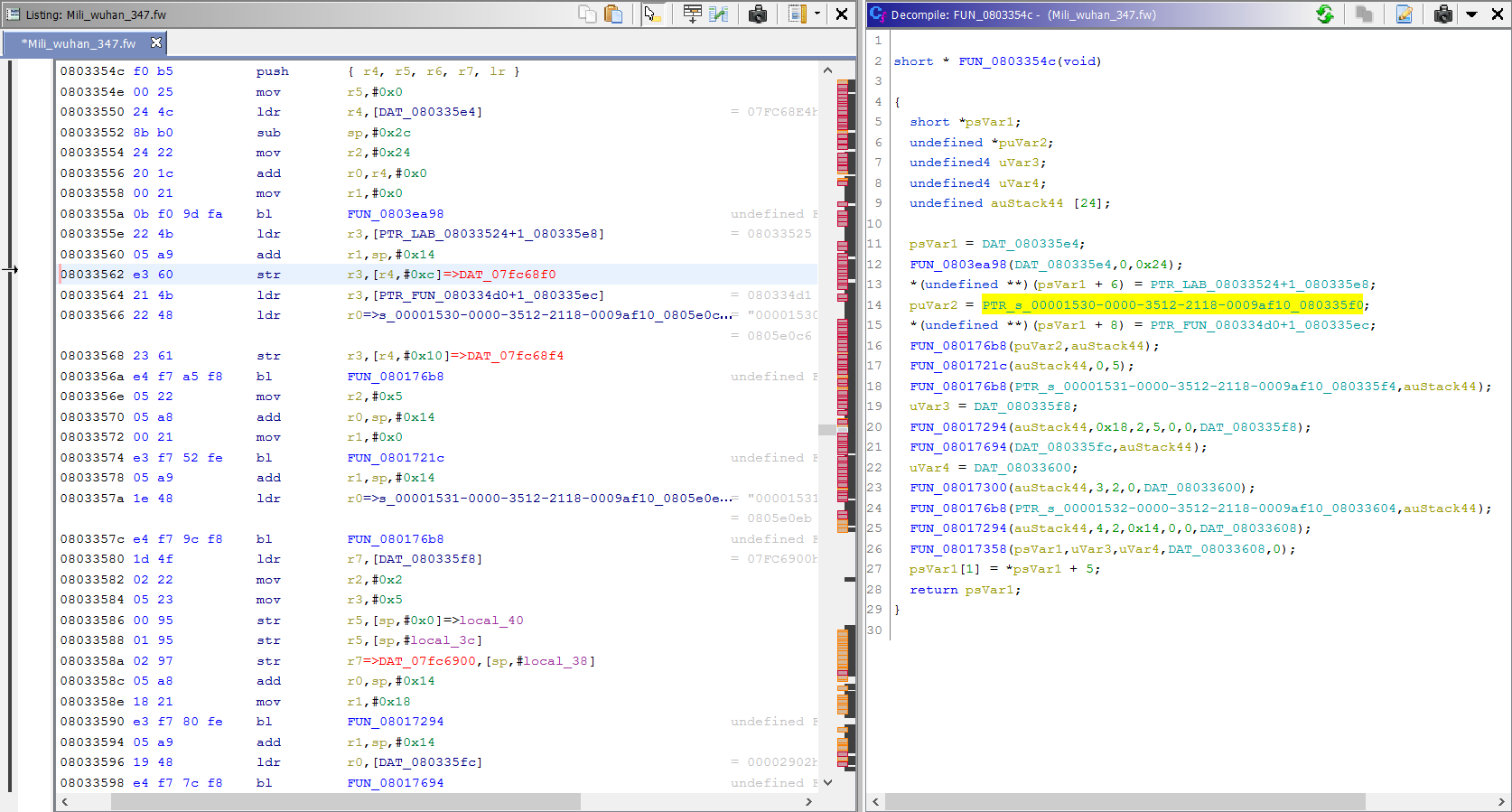

The best idea would be to start with a service UUID that we know what’s doing. Therefore let’s use the same service that’s used to upload the firmware. We are going to look for 00001530-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700 that has two characteristics: 00001531-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700 acting as control channel and 00001532-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700 used as data channel to send the firmware.

Of course finding the UUID in the image was not hard, and we quickly managed to find the corresponding function.

The service UUID is being assigned to the puVar2 local variable, and its used to call the FUN_080176b8(puVar2,auStack44) function. auStack44 is another local variable – an array of 24 elements. This function is also called with both characteristics UUIDs. After calling this magical function, the auStack44 is used in later functions. When we take a look into how this function is implemented it becomes obvious that this function parses the given UUID to a binary form. The string validation code gave it away:

// ...

iVar3 = FUN_0803eb78();

if ((((iVar3 == 0x24) && (pbParm1[8] == 0x2d)) && (pbParm1[0xd] == 0x2d)) &&

((pbParm1[0x12] == 0x2d && (pbParm1[0x17] == 0x2d)))) {

// ...

This if statement checks if the hyphens - (0x2d in ASCII) are at expected positions (8, 13, 18, 23 counting from 0). In the first condition we are using 0x24 (36) which so accidentally is the number of characters in a UUID. Let’s check whether the FUN_0803eb78() is actually a variant of strlen().

int FUN_0803eb78(int iParm1)

{

int iVar1;

int iVar2;

iVar1 = 0;

do {

iVar2 = iVar1;

iVar1 = iVar2 + 1;

} while (*(char *)(iParm1 + iVar2) != '\0');

return iVar2;

}

Well, Ghidra has not correctly guessed the function arguments. If we adjust the function’s signature we will get much better code:

size_t strlen(char *str)

{

size_t iVar1;

size_t iVar2;

iVar1 = 0;

do {

iVar2 = iVar1;

iVar1 = iVar2 + 1;

} while (str[iVar2] != '\0');

return iVar2;

}

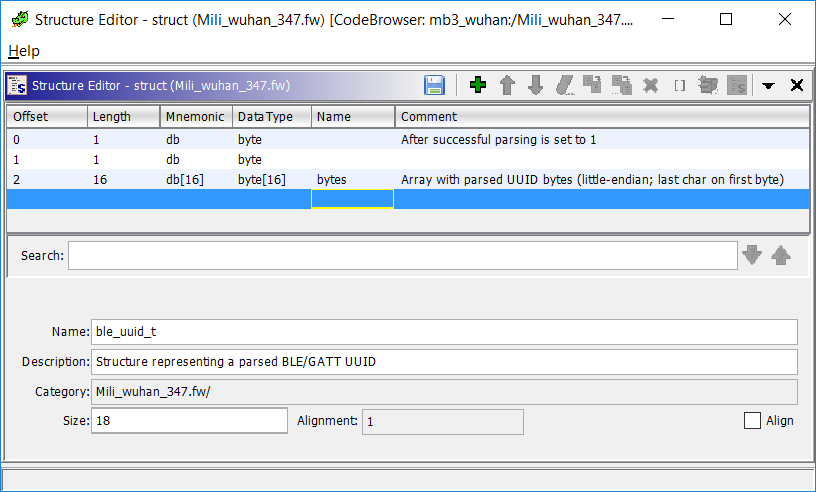

Ups, I’ve got a little ahead of myself 😅 So the UUID parsing function converts (case-insensitive) hexadecimals into numerical representation,

writing it to the buffer passed as second argument. But whats wired, it doesn’t store the parsed data right at the beginning. It always writes 1 at the beginnig of the buffer once the parsing has completed. To keep things clear let’s define a structure for that parsed UUID type and rename this function to ble_uuid_parse().

So what happens with those parsed UUIDs? The service UUID is passed to FUN_0801721c(uuid,0,5) and that’s all. Right after that we are parsing the UUID of the first characteristic. I think that this function creates the service, but currently I have no clue what the remaining params mean… I’ve renamed that function to ble_service_create__GUESS() for now…

So once we’ve parsed the UUID of the first characteristic (1531) we are calling FUN_08017294(&uuid,0x18,2,5,0,0,DAT_080335f8). The same function is also called for the second characteristic (1532), but with different arguments. Hmmm…

Let’s summarize what we know about those two characteristics:

00001531-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700- properties: NOTIFY, WRITE

- contains a

0x2902descriptor - second argument is

0x18 - fourth argument is

5

00001532-0000-3512-2118-0009af100700- properties: WRITE NO RESPONSE

- no descriptor

- second argument is

4 - fourth argument is

0x14

Those properties got me really interested, so I did some digging on the web. I was blessed when I’ve found following lines in BlueZ source code:

/*

* GATT Characteristic Property bit field

* Reference: Core SPEC 4.1 page 2183 (Table 3.5: Characteristic Properties

* bit field) defines how the Characteristic Value can be used, or how the

* characteristic descriptors (see Section 3.3.3 - page 2184) can be accessed.

* In the core spec, regular properties are included in the characteristic

* declaration, and the extended properties are defined as descriptor.

*/

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_BROADCAST 0x01

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_READ 0x02

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_WRITE_WITHOUT_RESP 0x04

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_WRITE 0x08

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_NOTIFY 0x10

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_INDICATE 0x20

#define GATT_CHR_PROP_AUTH 0x40

Now we are confident that the second argument encodes the characteristic properties. We are getting it! I’ve already named this function ble_characteristic_create().

Moving on to next call: FUN_08017694(DAT_080335fc,&uuid). This one’s slightly different. The first argument points to 00002902h but of unknown type.

But I’ve just wrote 0x2902 just a moment before – that’s the value of the descriptor! When we truncate the value to 2 bytes (short) using little-endian we will end up with this exact value. Looking at the body of this function (after correcting the signature):

void FUN_08017694(ushort uParm1,ble_uuid_t *out_uuid)

{

*(ushort *)out_uuid->bytes = uParm1;

out_uuid->field_0x0 = 0;

return;

}

I was wrong: I’ve mentioned previously that 1 was written at the beginning of our ble_uuid_t structure as a result of a successful parse. Now we are writing 0 there so this is clearly not the case, but please note that the conditions have also changed as we are not storing the full UUID, only the short word.

I’m getting pretty confident that this value is used to distinguish between those two conditions, so let’s name this field type.

Now rename FUN_08017694() to ble_uuid_from_short() and to stay consistent replace ble_uuid_parse() with ble_uuid_from_string().

I’d like to see where ble_uuid_from_short() is called from, but first let us finish what we’ve started. We have parsed the descriptor’s 16-bit UUID and which is followed by FUN_08017300(&uuid,3,2,0,DAT_08033600).

I’m pretty sure you’ve got the idea what this function does, so let’s give it a proper name 🙂

Not only strings matter

We’ve already identified two ways to create instances of ble_uuid_t – from ASCIIZ string and 16-bit unsigned integer. This means that we can search for other services and characteristics that where previously out of our reach (not exposed as strings).

What’s more beautiful is the fact that those short UUIDs are standarized so we can identify them rather quickly 🙂 So let’s take a random reference to ble_uuid_from_short() and work on it.

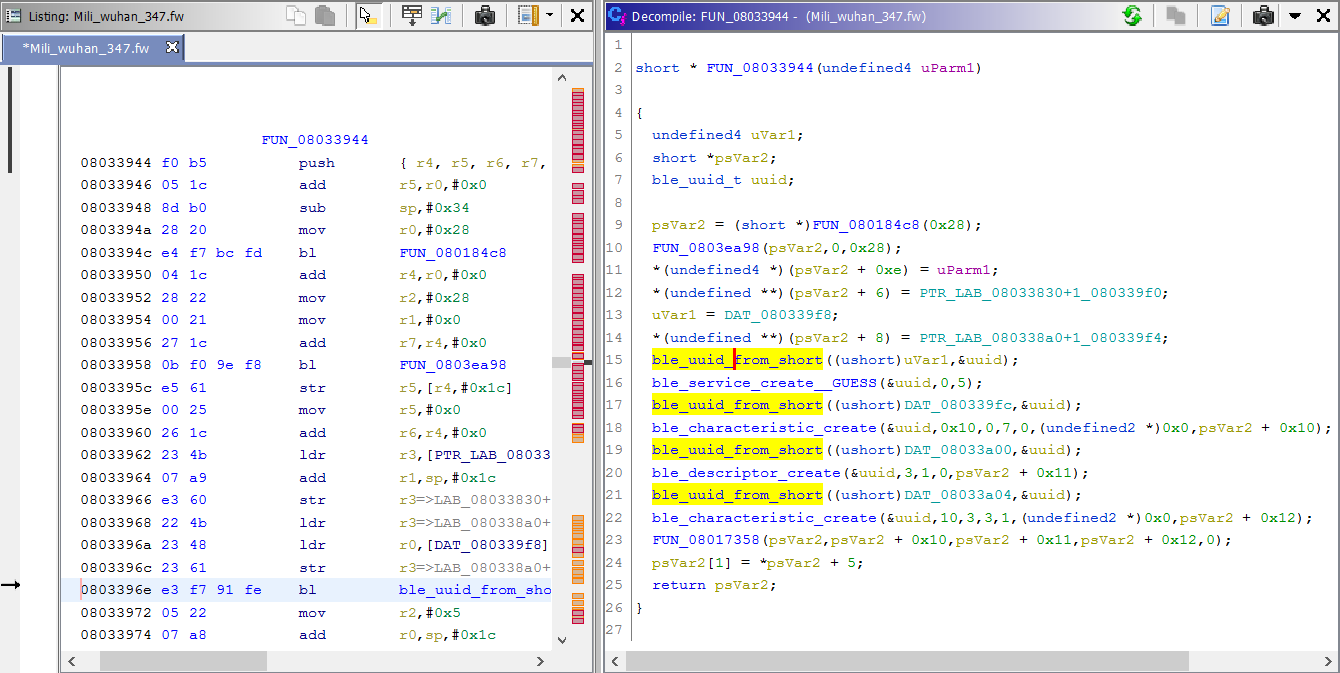

Look at this beauty – its already done! The value of DAT_080339f8, that’s gets assigned to uVar1, is equal to 0x180D. Once we look up this UUID in GATT Services registry, we know that this is the Heart Rate Service – piece of cake. So we can rename this function to indicate that it creates/initializes the heart rate service.

There’s one more thing that I would like to address in my upcoming blog post, but in the meantime I’ll leave it as a small exercise for the reader: look at the FUN_08033944() function – there’s a pretty common pattern at the beginning. Can you guess what both first functions might do by just looking at how they’re used? This should be a no-brainer if you used WinAPI before 😉